useState() In Depth

You must learn Component Rendering before getting into this chapter.

Batching

Be sure to check out this awesome post by Dan Abramov about batching! Most of the information in this section is simply a rephrasing of the ideas presented in the post.

Have you ever wondered about the difference between "declaring two states" and "declaring one state with two properties"? For example:

import { useState } from 'react'

// Two states

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(true)

const [data, setData] = useState(null)

// One state with two properties

const [state, setState] = useState({

loading: true,

data: null,

})

In most cases, it doesn't matter. We're saying this because React batches state updates by default.

In React, "batching" refers to the process of grouping multiple state updates into a single update. Before React 17, only the updates in React event handlers are automatically batched. Starting from React 18, all updates are batched by default.

What are React event handlers?

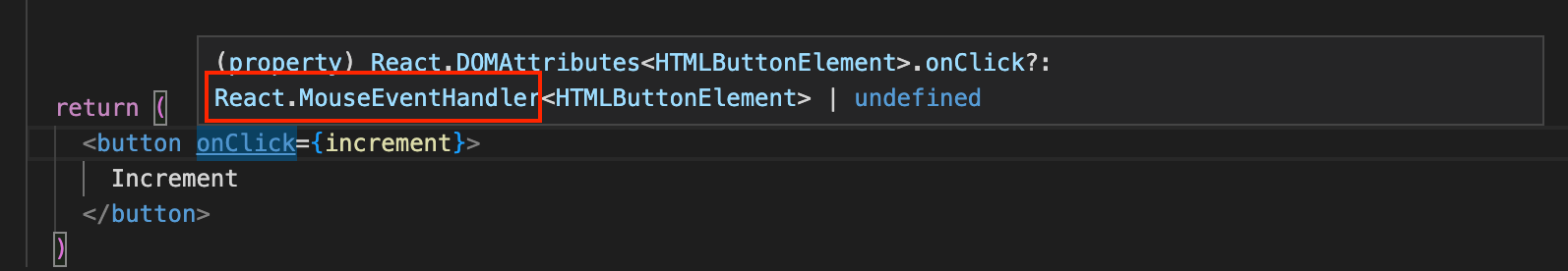

React event handlers are those things that come with React.[Something]EventHandler you see in VSCode when you hover on a handler prop:

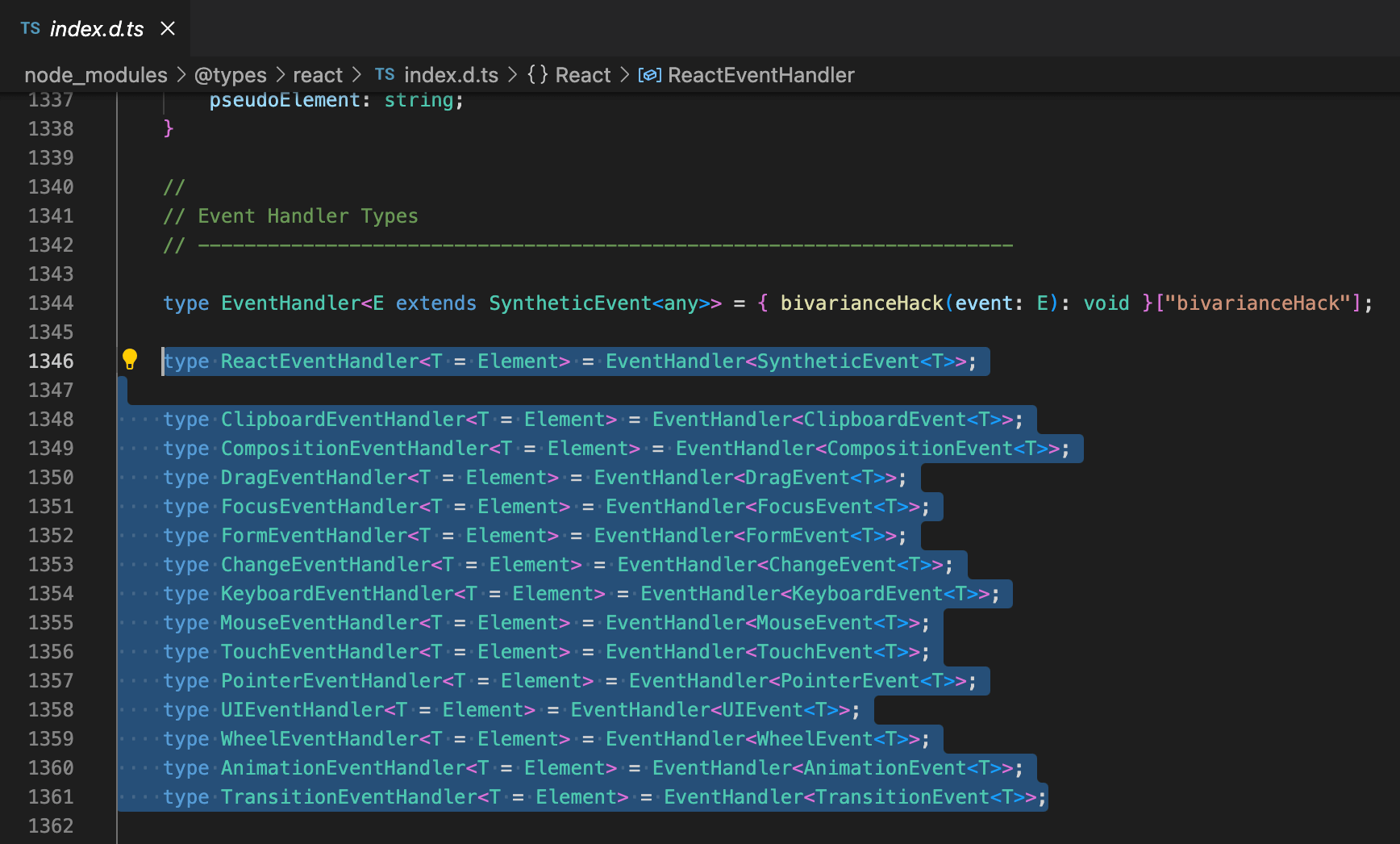

You can also see all the types in the declaration file:

React already handles most of the native HTML events, such as onClick(), onChange(), onBlur(), onDrag(), onSubmit(), etc. Life-cycle hooks like componentDidMount() and useEffect() are also considered React event handlers.

To understand how batching works, please take a look at the following example:

import { useState } from 'react'

const [name, setName] = useState('')

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const updateData = () => {

setName('A')

setCount(1)

}

In the above example, we might expect the component to re-render twice after updateData() is called because two separate setState() calls are made within updateData(); but in this example, the component will only re-render once.

Before explaining why is this happening, let's take a look at another example:

import { useState } from 'react'

const [name, setName] = useState('')

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const updateData = () => {

setName('A')

setCount(1)

setName('B')

setCount(2)

setName('C')

setCount(3)

}

In the above example, even though so many setState() are called, the component is still going to re-render once after updateData() is called.

Why?

It actually makes sense if we think about it. In the above example, we don't want users to see flickers when count is being updated from 0 all the way to 3. Since we know that the last value being passed to setCount() is 3, we can simply skip over all previous values and directly set count to 3. The same approach can be applied to name as well.

Additionally, after all update schedulers have been processed, React knows that the states to be updated are name and count. To minimize the number of re-renders and avoid any flicker that users might notice, React updates them both at the same time instead of individually.

The following video illustrates how states are updated in the above example. While the implementation may not be the same as React, it should give you a general understanding of how the render cycle works within a component.

If you're interested in how state updates are processed in React, please refer to the official documentation.

- Before the first render:

- All states in a component are stored in an imaginary object called

states. - An imaginary object called

updateSchedulersis created to hold all of the unprocessed update schedulers. - An imaginary object called

patchesis created to hold the values ofstatesfor the next render.

- All states in a component are stored in an imaginary object called

- Every time

setState()is called, the parameter (a value or a function) is pushed to the corresponding array inupdateSchedulers. - For each state, React evaluates the output based on the update schedulers and put it in

patches. Once all update schedulers have been processed, React copies all the properties frompatchestostatesand clearsupdateSchedulersandpatches.

After that, React updates the DOM nodes based on the values in states, and then waits for the next opportunity to process update schedulers.

Updater Functions

In React, an updater function is a function that is passed to setState() as an argument. It is useful when we need to update the state based on its previous value, or when the state is a non-primitive value like an object or an array.

For example, consider the following code:

import { useState } from 'react'

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const updateCount = () => {

setCount(1)

// `prevCount` will be `1`.

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 2)

}

In the above example, we first call setCount(1), which will update the value of count to 1 in the next render. Then, we call setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 2), which means "give me the last value being passed to setCount(), and update the value of count to (that value + 2)". Thus, in this example, count will be updated to 3 after updateCount() is executed.

Great, now let's take a look at another example:

import { useState } from 'react'

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const updateCount = () => {

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 1)

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 2)

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 3)

setCount(4)

}

In the above example:

- An updater function is used before any value is passed to

setCount(). In this case, React will use the current value ofcount, which is0, as the previous value. This means theprevCountin the firstsetCount()will be0, which will update the value ofcountto0 + 1. Thus,1will be the next value ofcountfor the next render. - When

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 2)is called, React knows that the last evaluated output insetCount()was1. This means theprevCountin the secondsetCount()will be1, which will update the value ofcountto1 + 2. Thus,3will be the next value ofcountfor the next render. - When

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 3)is called, React knows that the last evaluated output insetCount()was3. This means theprevCountin the thirdsetCount()will be3, which will update the value ofcountto3 + 3. Thus,6will be the next value ofcountfor the next render. - When

setCount(4)is called, it overwrites the next value ofcountwith4.

Therefore, the value of count will be 4 after updateCount() is called.

Fixed Value or Updater Function?

In most cases, it makes no difference. Many developers use updater functions frequently because updater function is a convenient and reliable way to update a state based on its current value without having to worry about anything else. However, depending on the situation, updater functions may not always be necessary. Consider the following example:

import { useState } from 'react'

const [user, setUser] = useState({

firstName: 'hello',

lastName: 'world',

})

const updateUser = (name, value) => {

const nextUser = {

...user,

[name]: value,

}

setUser(nextUser)

}

In the above example, updateUser() is still guaranteed to have the latest value of user, even if updater functions are not being used. This is because user is a state, changing it will cause the component to re-render, causing updateUser() to be redeclared. But it's still okay if you prefer using updater functions everywhere; usually it won't break anything!

One of the benefits of using updater functions is that it allows us to update a state based on its current value, even when it's inconvenient to access the state. For example:

import { useState, useCallback } from 'react'

const [count, setCount] = useState(0)

const increment = useCallback(() => {

setCount((prev) => prev + 1)

}, [])

In the above example, count will still be correctly updated even though increment() is wrapped inside a useCallback() without any dependencies thanks to the use of an updater function. This makes updater functions particularly useful when a function is being passed as a prop to memoized children.